The Illegitimacy of Violence, the Violence of Legitimacy

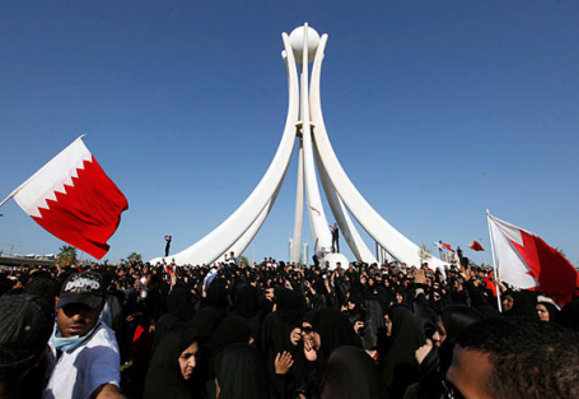

“Those who said that the Egyptian revolution was peaceful did not see the horrors that police visited upon us, nor did they see the resistance and even force that revolutionaries used against the police to defend their tentative occupations and spaces: by the government’s own admission, 99 police stations were put to the torch, thousands of police cars were destroyed, and all of the ruling party’s offices around Egypt were burned down. Barricades were erected, officers were beaten back and pelted with rocks even as they fired tear gas and live ammunition on us . . . if the state had given up immediately we would have been overjoyed, but as they sought to abuse us, beat us, kill us, we knew that there was no other option than to fight back.” – Solidarity statement from Cairo to Occupy Wall Street, October 24, 2011

The Illegitimacy of Violence, the Violence of Legitimacy

CrimethInc. Ex-workers Collective

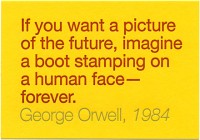

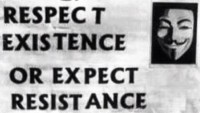

What is violence? Who gets to define it? Does it have a place in the pursuit of liberation? These age-old questions have returned to the fore during the Occupy movement. But this discussion never takes place on a level playing field; while some delegitimize violence, the language of legitimacy itself paves the way for the authorities to employ it.

“Though lines of police on horses, and with dogs, charged the main street outside the police station to push rioters back, there were significant pockets of violence which they could not reach.” – The New York Times, on the UK riots of August 2011

During the 2001 FTAA summit in Quebec City, one newspaper famously reported that violence erupted when protesters began throwing tear gas canisters back at the lines of riot police. When the authorities are perceived to have a monopoly on the legitimate use of force, “violence” is often used to denote illegitimate use of force—anything that interrupts or escapes their control. This makes the term something of a floating signifier, since it is also understood to mean “harm or threat that violates consent.”

This is further complicated by the ways our society is based on and permeated by harm or threat that violates consent. In this sense, isn’t it violent to live on colonized territory, destroying ecosystems through our daily consumption and benefitting from economic relations that are forced on others at gunpoint? Isn’t it violent for armed guards to keep food and land, once a commons shared by all, from those who need them? Is it more violent to resist the police who evict people from their homes, or to stand aside while people are made homeless? Is it more violent to throw tear gas canisters back at police, or to denounce those who throw them back as “violent,” giving police a free hand to do worse?

In this state of affairs, there is no such thing as nonviolence—the closest we can hope to come is to negate the harm or threat posed by the proponents of top-down violence. And when so many people are invested in the privileges this violence affords them, it’s naïve to think that we could defend ourselves and others among the dispossessed without violating the wishes of at least a few bankers and landlords. So instead of asking whether an action is violent, we might do better to ask simply: does it counteract power disparities, or reinforce them?

This is the fundamental anarchist question. We can ask it in every situation; every further question about values, tactics, and strategy proceeds from it. When the question can be framed thus, why would anyone want to drag the debate back to the dichotomy of violence and nonviolence?

The discourse of violence and nonviolence is attractive above all because it offers an easy way to claim the higher moral ground. This makes it seductive both for criticizing the state and for competing against other activists for influence. But in a hierarchical society, gaining the higher ground often reinforces hierarchy itself. …more

Add facebook comments

Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment