Time to change U.S. policy toward Saudi Arabia

Time to change U.S. policy toward Saudi Arabia

By Caitlin Fitz Gerald – Special to CNN – 28 September,, 2011

American foreign policy is often torn between shared values and strategic interests. Nowhere is the divide more pronounced than in U.S. dealings with the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Although Saudi Arabia has an egregious record on human rights, a major arms deal is being finalized between the country and the U.S. Indeed, Saudi Arabia appears positioned to remain a stable center of U.S. policy in the region, now more than ever.

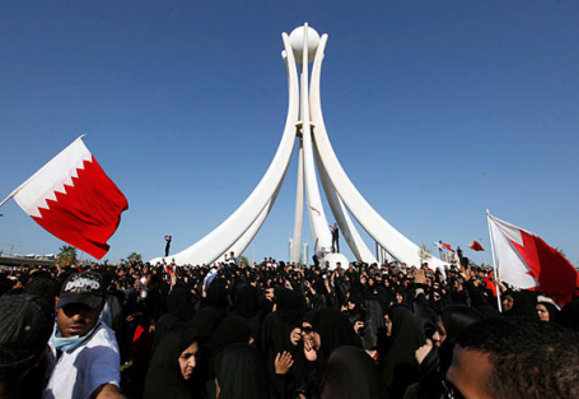

Saudi Arabia’s interactions with its restive neighbors have been reliably counterrevolutionary. Saudi Arabia has historically preferred Yemen divided and weak. Although divisions within the regime on the best approach to Yemen are clear, Saudi Arabia has shown a consistent willingness to intervene in Yemen’s affairs. North of the Kingdom in Jordan, where stalled political reforms and a struggling economy have led to regular protests, the Saudi regime has offered economically advantageous membership in the Gulf Cooperation Council and at least $400 million in grants to support the country’s economy and reduce its budget deficit. Additionally, Kingdom forces headed up an intervention in Bahrain in March, on behalf of their allies, the ruling al-Khalifa regime.

Saudi troops helped the Sunni leaders crack down on the Shia protests and may have assisted in the destruction of a number of Shiite mosques in the country. This assistance not only helped restore stability to the closely neighboring island, but also may have served as a message to the Kingdom’s own Shia population, which has long been the subject of severe discrimination by the Wahhabi sect that dominates the Saudi religious establishment. In recent years, there has been a renewal of small Shia protests in Saudi Arabia, but public protest remains illegal. The government aggressively clamps down on protest movements, and those arrested often disappear into the prison system. The only man to appear for a planned day of protests on March 11 in Riyadh was arrested; he remains imprisoned with no access to legal representation.

Saudi Arabia’s record on human rights is dismal . The plight of the country’s foreign domestic workers is so bad that Indonesia this year barred its citizens from working there after a particularly serious incident. Laborers not only work long hours for little pay under draconian sponsorship laws, but abuse is common, redress virtually unknown and a worker is more likely to be convicted for standing up for herself than to see her employer convicted for abusing her. Saudi citizens cannot rely on the rule of law either, as the legal system is still built largely on un-codified religious law and royal decree. Even codification efforts seem aimed toward formalizing injustice. Despite some recent changes, women in Saudi Arabia have diminished legal standing; a woman’s voice carries half the weight of a man’s in court proceedings and women require the supervision of a male family member for many activities. They are also not permitted to drive, which is the only rights issue for which U.S. politicians have applied any public pressure on the Saudi regime.

Nevertheless, last fall, the U.S. came to an agreement with Saudi Arabia on a $60 billion arms deal, the biggest such deal in U.S. history. It includes a large package of new fighter jets, upgrades to older jets and a variety of attack helicopters, as well as equipment, weapons, training and support for all systems. It hasn’t been finalized, but Congress raised no objections when the deal was reviewed last fall. In fact, in July there were reports that the deal was being expanded to include an additional $30 billion to facilitate upgrades to the Saudi Navy. An agreement of this scope and magnitude shows a clear commitment by the United States to its future relationship with the Kingdom. Upgrading their fleet will allow them to take a stronger posture against Iran and those attack helicopters will be useful for limiting spillover from the chaos in neighboring Yemen.

While our Secretary of State and various members of Congress are lobbying the Saudi regime to allow women the relatively minor freedom of driving, others in our government are negotiating billions of dollars in arms sales to the Kingdom and watching quietly as Saudi troops clamp down on their neighbors’ democratic reform movements. Our actions speak for themselves. With Egypt in a turbulent transition and unrest sending tremors through the whole region, the U.S. is banking on Saudi Arabia to help contain the chaos in Yemen, keep Bahrain a quiet home for the busy Fifth Fleet of the U.S. Navy, prevent Iran from dominating the region, and of course, keep the oil flowing. There is also a bonus effect of filling any potential void in military spending to our massive defense industry that might be left by anticipated cuts to domestic defense spending. We have $60-90 billion in military hardware riding on Saudi Arabia – never mind a substantive discussion of human rights or democratic reform.

This is problematic in several ways. It has become a tired refrain in international policy circles: Why do we have a responsibility to protect the civilians of Libya, but not the people of Saudi Arabia? Why do we oppose the extremist ideas of Iran or the Taliban, but remain silent while Saudi Arabia uses its wealth to spread Wahhabist ideology around the world? We have a clear credibility gap. We can only talk of democracy and universal rights while materially supporting their biggest opponents for so long before our words are rendered meaningless. Our stance on these issues should be clear and consistent, even if our approach to promoting that stance must be different for different states. Otherwise, on any occasions when we want to spark a discussion or spur action on these issues, our opinion will be given significantly less weight.

The strategic interests that drive our relationship with Saudi Arabia now may seem more important in the short-term, but in the long-term, what has the greatest potential to serve our interests: the arms we can sell to Saudi Arabia or the example of free expression and assembly we can set? What is a bigger long-term threat: Iran, with its devastated economy and ever-waning legitimacy, or the extremist ideology Saudi Arabia spreads through the mosques and schools it builds and funds all over the world?

For many years, the U.S. turned a blind eye to the abuses of the Mubarak regime in Egypt in a trade-off for a perceived security advantage only to be left stumbling for a reaction as the Egyptian people took it upon themselves to oust him. Saudi Arabia is still a long way from this stage, and American support will make that distance longer, but eventually change will come, in one way or another. Maybe it will be a peaceful democratic transition; maybe it will be a coup from within the dynasty or from the Wahhabi religious establishment. Do we want to have an unblemished record of support for a repressive regime when that time comes? Or would we rather have the credibility of a nation that encouraged reform and expanded liberty and that might be in a position to influence or lend assistance to a genuinely democratic movement? ...source