Bahrain and the “Arab Spring”

Bahrain’s contribution to the Arab Spring

The Bahraini government used the spectre of sectarian violence to justify their crackdown on peaceful protesters. by Lamis Andoni Last Modified: 30 Aug 2011 14:07 – AlJazeera

Arab silence on the continued repression of the Bahraini people is a shameful episode that does not fit the era of the Arab revolution. It is also a testimony to the determination of the US-backed Gulf political order – that is leading the effort to place a cap on change in the Arab World – to prevent the revolution from reaching its member states.

But in a wider context, the silence, or at least the lack of adequate solidarity with Bahraini revolutionaries, is indicative “of fear” of the Iranian and Shia influence on the predominantly Sunni Arab world. The Gulf states made sure to portray the protests as a sectarian Shia plot in order to obscure the Bahraini movement’s political message of justice and equality.

The relative success of isolating the Bahraini movement by fomenting sectarian fears is regretfully a sign that the Arab Spring has not succeeded in doing away with sectarian prejudices that are not only impeding effective solidarity, but threaten to tear up some Arab uprisings.

Part of the problem is that the Arab uprisings have not yet radically changed the official Arab order that consists of governments that have fed sectarian divisions to ensure their longevity. The fact that Bahrain’s population is 70 per cent Shia but is ruled by an authoritarian Sunni royal family have made it possible for governments to claim an Iranian scheme to undermine the stability of the Gulf and consequently the Arab world.

Some Iranian statements, such as the infamous quote by former Iranian Shura Council speaker Akbar Nateq Nouri, that Bahrain is part of Iran, did not help. In other words, the Bahraini movement for change became partly a victim to the geopolitical contest between Iran and Saudi Arabia over the strategically located country. But mostly the open conspiracy against the Bahraini movement was precisely due to its indigenous, popular and political nature – a fact that was clear from the very outset.

Historic struggle

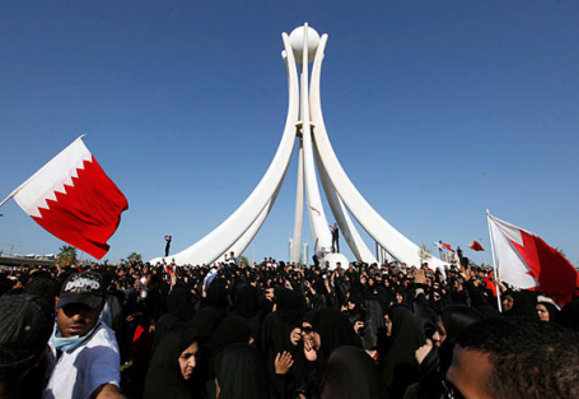

If anything, the Bahraini protests that started last February were in effect a continuation of a long-standing historic struggle for political freedoms that preceded the tiny country’s independence from Britain in 1971.

Bahrain was affected by the anti-colonialist Pan Arab and leftist wave that swept the Arab world in the fifties demanding independence from British rule and the formation of an elected consultative council. The dream was about to be fulfilled after independence when in 1973 Emir Issa Ben Salman Bin Khalifa approved a constitution allowing elected parliament (74 per cent were elected and around 26 per cent were appointed by the Emir).

Click for more of Al Jazeera’s special coverage of the government crackdown on protests in Bahrain

The parliamentary experiment came to a halt when the Emir dissolved parliament, citing fears of sectarian strife – a claim refuted by the opposition at the time – and proceeded to rule by decree.

An all-out campaign of arrests and torture followed, forcing many Bahraini intellectuals and activists to seek asylum in other countries, particularly in Europe, including the Eastern bloc, away from reach of their government.

The Bahraini government, which by then had become a close ally of Washington, tried to impose subordination by pursuing a combined policy of repression and discrimination against the Shia. The 1979 Iranian revolution spurred the emergence of movements based on religious identity (Sunni and Shia alike), especially after the blow dealt to the secular opposition.

But the major demands of the Bahraini opposition revolved around equality and a restoration of parliamentary life – although a pro-Iranian Shia group did call for extending Tehran’s rule to the tiny country.

In 1994 an uprising, led mainly, but not exclusively, by Shia parties finally culminated in the signing of the National Action Charter (NAC) in 2001. It represented an historic accord between the opposition and the royal family based on the restoration of parliamentary elections and political reforms.

But in spite of two parliamentary elections, Hamad Ben Issa Al Khalifa, who succeeded his father and changed his title to king from emir (prince) – a move that was supposedly aimed at establishing a constitutional monarchy – continued the regime’s authoritarian and repressive policies.

Thus it was natural that Bahrainis were inspired early on by the success of the Arab uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt to pursue a new stage of their struggle. As early as February 14, Bahraini youth followed the example of their peers in other Arab countries by staging protests and sit-ins demanding constitutional and political reforms.