The War on Drugs and the Mexican Movement to End It

The War on Drugs and the Mexican Movement to End It

“It’s a Welcome Escape From the Seemingly Insurmountable Sectarianism that Has Plagued Social Movements for Centuries”

By Quincy Saul – Special to The Narco News Bulletin – August 6, 2011

The forty year anniversary of the war on drugs came and went this summer without any mention of the most significant movement to end it.

The Global Commission on Drug Policy released a report in June with a clear and succinct conclusion: “The global war on drugs has failed.” The US government has now spent about a trillion dollars on this war, but drug consumption has increased and drug-related violence and incarceration have spiraled ever further out of control. Signed by a wide diversity of prominent names such as Paul Volcker, Ernesto Zedillo, Carlos Fuentes and Kofi Annan, the report went on to accuse the United States of “drug control imperialism.”

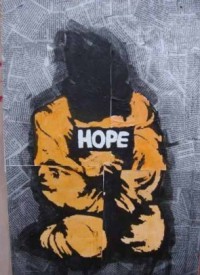

More than any other country, Mexico is dying from the sins of the war on drugs. As the bottleneck of the drug trade for all of the Americas, almost 50,000 have been killed in drug-related violence in Mexico in the last six years alone, with the numbers of dispossessed and disappeared mounting ever higher. It is not entirely surprising then, that the first mass movement to end the drug war has arisen in Mexico. More surprising is the almost total boycott in the United States and international media of this movement.

The Movement

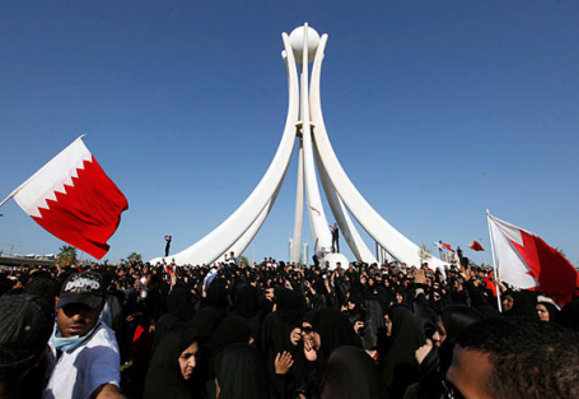

Seen from the outside, the current movement to end the war on drugs in Mexico began suddenly. The brutal murder of the son of a prominent poet named Javier Sicilia prompted him to write a call to action urging all Mexicans to take to the streets to end the drug war. His voice reached and touched millions. Within days, tens of thousands had filled the centers of forty major cities, calling for the legalization of drugs and the demilitarization of their country.

Popular mobilization has been sustained since then through two major actions involving all demographics of Mexican society. Led by Sicilia, a week-long march to end the drug war from the city of Cuernavaca to the nation’s capital culminated on May 8th when 100,000 people filled the central square of Mexico City. That same weekend, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation led a silent march of tens of thousands out of the mountains, occupying the city of San Cristóbal de las Casas.

Several weeks later, the mobilization continued with a “caravan of solace,” in which tens of thousands more participated. The caravan traveled from Cuernavaca through a dozen major cities, for the first time sharing and organizing the pain which until now most Mexicans have suffered in fear and isolation. The caravan culminated in the infamous Ciudad Juárez. Renowned as the most violent city in the world, the caravan inscribed a fresh, new and indelible chapter in the city’s history. In the words of Antonio Cervantes, a participant in the caravan, on the eve of its arrival, “we are going to occupy Ciudad Juárez peacefully… We are going to fill the most violent city on earth with humanity and desire for life.” The nonviolent occupation of Juarez concluded peacefully with the reading of drafts of a pact which includes demands and a program of action.

By any measure, this movement is a game changer. Calling itself the “Movement for Peace with Justice and Dignity,” it is the first nonviolent mass movement in the history of Mexico. Javier Sicilia is doing what all previous leaders in Mexico have failed to do—unite all sectors of society into a sustained movement in which all groups see their interests reflected. “We have to return to the era of Gandhi, to the era of Luther King,” said Sicilia, who on numerous occasions has promoted the legacy and tradition of civil disobedience. Slowly but surely, this movement is standing up, preparing itself to end this war, with or without the agreement of the government. A placard in the city of Chihuahua urged the caravan, “If Crime is Organized, then Why Not Us?”

Media Silence

With a few isolated exceptions, there has been a complete boycott by the US media of this movement. International press has been barely better. For the English speaking world, only a few small online news sources like Narco News are paying any attention.

Reporting on the horrific violence of the drug war in Mexico is abundant and detailed both in mainstream and alternative media. So why the silence about a movement to end it? After all, the development and consequences of this movement are guaranteed to have effects in the United States and around the world. Is it that the abundance of popular uprisings this year have newsrooms swamped, and that this one is just slipping through the cracks? Months into the movement, such arguments are no longer adequate. When a story of this magnitude consistently fails to break headlines for such a long period, we must ask if there are other reasons, other interests behind the silence. …more