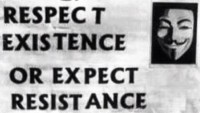

Which one came first twitter ot the revolution?

The Middle Ground between Technology and Revolutions

Aaron Bady 08/26/2011

Social media didn’t cause the revolutions in Egypt and Tunisia, but it did achieve unique visibility.

Is there still a debate on whether social media can cause revolutions? If this was ever a serious question, it was mainly an argument between straw men: on the one hand, wild idealists who saw the internet as an all-encompassing force for freedom and on the other, the crusty curmudgeons who fear technology and pooh-pooh the idea that social media is good for anything but posting pictures of cats. NYU professor Jay Rosen characterized the debate as “Wildly overdrawn claims about social media, often made with weaselly question marks (like: ‘Tunisia’s Twitter revolution?’) and the derisive debunking that follows from those claims (‘It’s not that simple!’)” and argued that these “only appear to be opposite perspectives. In fact, they are two modes in which the same weightless discourse is conducted.”

I think we can safely put that debate aside. While Malcolm Gladwell made a lot of noise last October by declaring that “the revolution will not be tweeted,” reporting like John Pollock’s “Streetbook” demolishes the idea that there is some intrinsic and impassable barrier separating “street” activism from the kind of “slacktivist” organizing of which Gladwell is so dismissive. But it’s worth noting that even the most visible “cyber-utopians” and “cyber-pessimists” seem to be converging on a point somewhere in the middle. In March, Clay Shirky significantly qualified the kinds of claims he makes for the centrality of social media—arguing that it is access to each other, not access to media, that makes revolutions—while Evgeny Morozov has pointed out that both he and Gladwell have been clear that the internet can be an effective tool for political change, as long as it is “used by grassroots organizations (as opposed to atomized individuals).” If you can see the fundamental divide between these arguments, you see more clearly than I do.

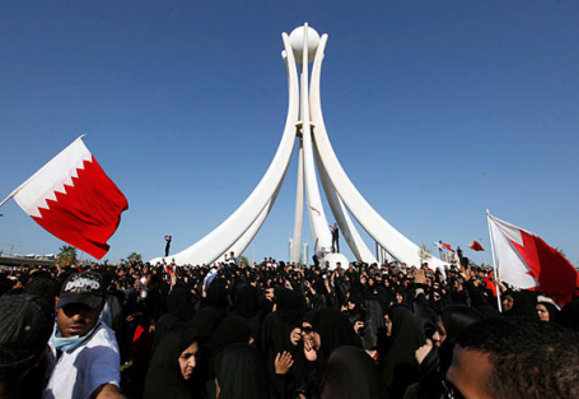

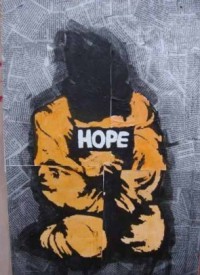

What’s different, I suspect, is that we can now ask the question in the past tense, and the answer is that middle ground onto which both sides are converging, a very middling “kind of, but not completely.” What happened in Egypt and Tunisia were revolutions, but they were obviously not caused by Facebook or Twitter: as Ramesh Srinivasan pointed out only 15% of Egyptians have Internet access, and only a small percentage use social media sites. But along with reporting like Pollock’s, the work done by people like Zeynep Tufekci, Samir Garbaya, and Ramesh Srinivasan allows us to stop talking, hypothetically, about “technology” and “revolutions” in the abstract, and to start looking at what it was about these revolutions and these regimes that gave these social media tools such potency, visibility, and usefulness. Which is all to the good. Talking about the technology risks making Facebook or Twitter the hero of the story, thereby turning our attention away from the courage and commitment of face-to-face organizers and masses in the street.

But while Malcolm Gladwell may still think that “the least interesting thing [about the protests in Egypt] is that some of the protesters may (or may not) have at one point or another employed some of the tools of the new media,” it still seems undeniable that social media has achieved a unique kind of visibility in the story of the “Arab Spring.” You cannot tell the story of Khaled Said, after all, without talking about social media: he was dragged out of a cybercafé and beaten to death for posting a video showing police corruption, whereupon pictures of his battered face became a mobilizing point for the Facebook group “We Are All Khaled Said,” moderated by Google executive Wael Ghonim. Ghonim’s declaration to Wolf Blitzer on CNN that “This revolution started online…on Facebook” is not really credible, of course; at most, Facebook organizing managed to build on and enhance the Kifaya movement, which started years ago. But if Facebook is not the whole story, it is certainly part of the story. And what are we to make of the story of the Egyptian newborn named “Facebook”? Or of photos like this one? ….more