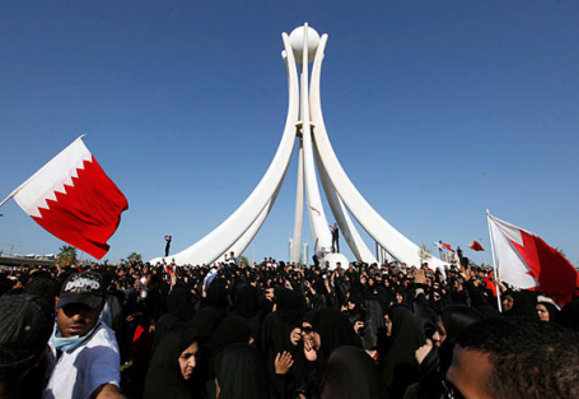

Dances on quicksand: US Pretense of Democracy – getting cozy with the Arab Spring

Third in a series of seven op-eds examining the history of US foreign policy in the Middle East

Dances on quicksand: US and the Arab Spring

Khaled Mansour – 7 Decemebr, 2013

It has been a truism for decades to attribute the drivers of US foreign policy in the Middle East to two realist drivers; free flow of oil from the major Gulf producers and Israel’s security, with the latter seen as part of the US power projection in this region since the cold war era and increasingly also a domestic policy concern since the late 1960s.

Glibert Achcar in his tour de force of the recent Arab revolutions in The People Want: A Radical Exploration of the Arab Uprising (University of California Press and Saqi Books, 2013), views US foreign policy in the region as an exclusive domain for the realists (who care most about the free flow of oil and Israel as a strategic asset in the Cold War and now the only reliable one in a shaky region).

In this he is supported by former assistant secretary of state for Near East affairs, Martin Indyk, who argues that unlike the balance the US had always to strike between the national interest and the nation’s values, “in the Middle East…every American president since Franklin Roosevelt has struck that balance in favour of the national interest, downplaying the promotion of America’s democratic values because of the region’s strategic importance.”

It has to be noted that national interest, according to Indyk who now works with the Brookings Institution, stands for economic and security interests which can be measured in the short term.

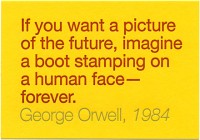

Timothy Mitchell, in his seminal work, Carbon Democracy (Verso Books, 2011), argued for seeing democracy, human rights and the Wilsonian tradition in general as instruments deployed to stabilise the capitalist project in the region, and the world at large, in a much more effective way compared to brutal autocracies. In other words, democracy and human right are necessary instruments sometimes.

Let us look more deeply into the vast oil question.

The US is the ultimate guarantor of energy supplies from the Middle East, which provides about a third of global oil production (nearly 14 percent of total global energy production) and is the main provider for Europe, China and Japan. The Arab region has about 50 percent of world oil reserves.

Although the US does not primarily depend on this oil for own energy needs, it is extremely important for main players in the world economy, whose financial health affects that of the US in the interdependent global economic environment. This policeman function should also provide Washington DC with a clout when negotiating trade and other economic issues with the rest of the industrialised world.

Historically, it was oil that attracted the US to the region, especially after WWII when the US became the region power broker and security guarantor. The 1956 Suez Crisis signaled the end of 40 years of imperial control by the French and the British following the 1904 Sykes-Picot agreement.

Saudi Arabia, the largest oil producer in the world, provides the best example of how American values can become so subservient to hard interests. With no constitution nor real parliament, the royal family exercises absolute authority, which is formally vested in the king but legitimated by an alliance with an extremely conservative clergy, which controls education, public space and is financially well-endowed.

Mitchell, and others, argue that this political and social arrangement in Saudi Arabia is not primarily natural or an expression of indigenous factors only, but has been as well built by external intervention, mainly British, and then sustained by the Americans who punished deviations from this model. …more

Add facebook comments

Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment