The eternal marriage between capitalism and democracy has ended

Slavoj Žižek: The eternal marriage between capitalism and democracy has ended

2 September 2013, by Harry Cross – Humanité

From the Humanité summer series Imaging a New World. Interview with Slavoj Žižek, Slovenian philosopher and psychoanalyst. According to him the historic era of capitalism is drawing to a close. The word “communism” should not be avoided when describing the horizon of our hopes.

After spending a considerable part of his intellectual formation in France, it is in Ljubljana, the city of his birth in 1949, where Žižek bases himself for his research. It is also from this town, when he is not fulfilling commitments around the world, that the Slovene iconoclast writes most of his books, now translated into dozens of languages. His polymorphic work draws on Lacan, Hegel and Marx, whose systems of thought in combination he believes offer an unrivalled means of understanding the antagonisms that span society. Žižek delivers an intellectual attack on numerous ideas that pose problems in contemporary reality: globalisation, capitalism, liberty and servitude, political correctness, Marxism, postmodernity, democracy, ecology… Described by his detractors from the left and the right as truculent and uncontrollable, Žižek is above all a thinker who does not abide by intellectual convention and practices. His conceptual constructions are rooted in a “living” Marxism (to use the well-chosen words of Sartre), a Lacanian passion and a Hegelian tropism. This construction rests in part in the digressions that he allows himself to come closer to the tensions of the real in its interwoven complexity.

You wrote in your most recent work that “the seizures of state power have failed miserably” and that you consider that “the left should dedicate itself to the direct transformation of social life.” Can these two not be intertwined?

Slavoj Žižek: I am in severe disagreement with several of my friends, notably in Latin America, who believe that taking power should no longer be a priority, and that the Bolshevik or “Jacobin” paradigm (in other words, the direct seizure of state power) should be abandoned in favour of instigating change in local communities. There is even the illusion that the state will disappear by itself. My position is entirely different. We must remain Marxist. The basic social antagonism is not found on the level of power and governance; it is the economic antagonism which expresses most directly the paradox of capitalism. The solution is not to be found in a movement of resistance against the state. That is not our greatest enemy. It is wrong to think that the solution is to keep a distance from the state, capital already exists a distance from the state! The enemy, for me, is this society in its actual mode of functioning and the economic domination it creates.

It is therefore firstly the role attributed to the state that you question, rather than the hypothetical opposition between civil society and the state?

Slavoj Žižek: Depriving oneself of the state can lead to worse scenarios. One left-wing legal theoretician told me that he had looked at all the legal cases in the United States in which local communities opposed the state. The neoconservative civil movement believes that the state should not interfere in civil affairs. Reactionary groups have therefore succeeded in banning homosexuality in schools to take but one example. In the United States, it is the state that defends certain fundamental liberties against pressure from local and civil neoconservatives.

Do you conclude from this that civil society is not necessarily endowed with good, universalist intentions, and that one of the functions of the state could be to contain, if not to supersede dogmatic authoritarianism?

Slavoj Žižek: Yes, we must not forget the fascist movements. Today, the great antimigrant movement born out of patriotism is a manifestation of civil society. The most radical conflict is not between state and subject, it is an economic conflict which can be dominated by the state. Maintaining a distance from the state means that we abandon control of the state to the enemy. It is true that within the structure of the state itself there is a form of domination. This should not stop us from considering how we can achieve many things with it. The tool is ambiguous, it can be dangerous, but it can also be a tool of social transformation.

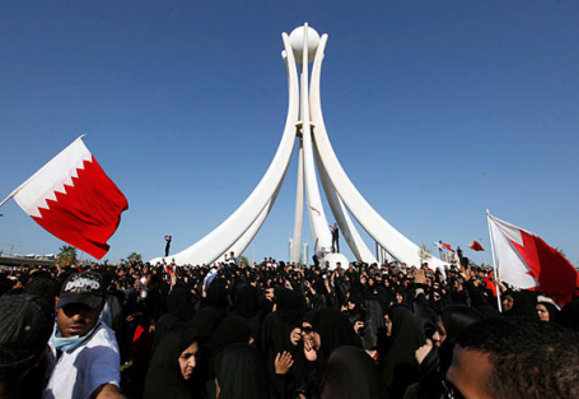

You seem at times sceptical regarding mass mobilisations. Do you thinks these “groups-in-fusion”, to use the expression of Sartre, are incapable of radically transforming the course of events?

Slavoj Žižek: The mass movements that we have seen most recently, whether in Tahrir Square or Athens, look to me like a pathetic ecstasy. What is important for me is the following day, the morning after. These events make me feel as one does when one awakes with a headache after a night of drunkenness. The major difficulty is in this crucial moment, when things return to their normal state of affairs, when daily life starts again.

Even if the promise of revolution is lost, do these movements not pre-empt history with the possibility of precipitating greater events?

Slavoj Žižek: Yes, but what is left of these great events? The success of these large ecstatic movements should be evaluated on the basis of what is left after they have gone. Otherwise we are in the back to the romanticism of ’68. It is what takes place next that interests me. The problem is knowing what are we are concretely doing today? That is why I admired the results of Hugo Chavez. We talk without end about the continuous auto-mobilisation of the masses. I do not want to live in a society in which I am obliged to be permanently politically mobilised. We have more and more the need for large social projects with concrete and lasting results.

You juxtapose the crisis of capitalism with an ecological crisis. What is this “ecological crisis” that you discuss at length in your In Defence of Lost Causes?

Slavoj Žižek: I do not like the mythology of the ecologist movement with believes in a natural equilibrium which was destroyed by human imperialism or destabilised by the exploitation of nature. I prefer left-wing Darwinism which argues that nature does not exist as a homeostatic order, a Mother Earth whose balance was disturbed by man’s intervention. That is a view that has to be abandoned. I think by contrast that nature is crazy, driven by natural catastrophes, and is one big chaos. This absolutely does not mean that we do not have to work to avoid catastrophe, quite the reverse, the situation is extremely worrying. But we must leave behind this ecological moralisation and the homeostatic perspective. Theology in its traditional form can no longer fulfil its primary function which is to impose fixed boundaries. Invoking God no longer works. By contrast, invoking Nature is beginning to fulfil this role. I do not have any grand answers to the problem but a first useful step would be to refuse the ecological “way of life”. This individualises the ecological crisis as evidenced in the urge to recycle. As if that will suffice to accomplish its purpose! That does nothing but replicate a permanent sense of guilt. I am much more interested in how we can organise to prevent future population movements tied to climate change. The answer to this question interests me more than endless talk about recycling.

You have always been concerned with the democratic question. Drawing as much on Plato as Heidegger you show its often illusory character. Is it time to seek its renewal, or do you believe in the straightforward abandonment of this idea?

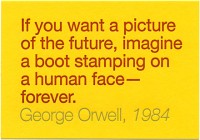

Slavoj Žižek: It all depends on what we mean by democracy. Democracy as it currently functions is being more and more called into question. It is one of the important lessons of Occupy Wall Street. Even if it did dissipate it had two correct intuitions. Firstly, it was opposed to being a “one issue movement”: it was a concrete denunciation of the fact that there is something seriously wrong in the actual economic system. Secondly, this movement showed that our existing political system is not strong enough to move effectively against these economic infringements. If we allow the current global system to develop by itself I expect the worst: new apartheids and new forms of social division. I believe that the eternal marriage between capitalism and democracy is over. It has only a few more years to hold out.

What then can replace this “empty shell”?

Slavoj Žižek: What we have on our hands is a democracy void of all significance. But I am not for brutally abandoning this idea. There are precise situations where I can be pro-democratic. In this sense I am not for the systematic rejection of elections. Sometimes they can be very fruitful, as in the Paris Commune, or if one was to imagine a victory of Syriza in Greece. It would be a beautiful democratic moment. But there is a democratic crisis to be overcome. Recall the shock in Europe when Papanderou proposed a referendum. Electoral choice is regularly manipulated in numerous ways, but it can happen that we are able to do things that are truly democratic. I am not therefore in principle against this idea.

You denounce a Europe voided of all “ideological passion”. What is the damage done by this, according to you, in its present form?

Slavoj Žižek: There are three Europes. The technocratic Europe is not bad in principal. But when that is all there is, the unity it offers is a mere façade and it is only capable of delivering the means of its own survival. The populist xenophobic Europe is violently anti-migrant. The biggest danger for me resides in the third Europe, which is the superposition of an economic technocracy (which is multicultural and liberal at the bottom) and an idiotic patriotism. Berlusconi’s Italy is a sinister example. By contrast, I have the impression that we as Europeans have had enough of continuous self-flagellation. We have to be able to defend and boast about what Europe is based on: its values rooted in equality, feminism and radical democracy. The great anticolonial movements were European in inspiration. Our only hope is to inspire another idea of Europe.

You are therefore advocating a new political voluntarism?

Slavoj Žižek: The imminent logic of history is not on our side. If we let it lean toward its natural tendency, history will continue to lead toward a reactionary authoritarianism. In that the analyses of Marx should be our starting point. This line must be pursued whilst considering also other questions, raised for example by the Italian autonomists, such as Maurizio Lazzarato, who argues that, in daily ideology, our servitude is presented to us as our freedom. He demonstrates how we are all treated as capitalists who invest in our lives. Indebtedness implies a functional discipline. It is today a new way of maintaining control over individuals, all whilst promoting the illusion of free choice. Even the fragility of our career path and chronic insecurity is presented to us a chance to reinvent ourselves every two or three years. And it works very well.

A series of intellectuals, of whom you are one, defend the idea that the communist idea is not yet exhausted. Does the idea has a future despite it frequently being the object of vulgar reductionism?

Slavoj Žižek: The axiom we have in common is to continue to use the word “communism” to describe the horizon of our hopes. Contemporary liberal anti-communists do not even have the conceptual ability to formulate a true critique of communism. The theory of the totalitarian temptation which is inherent in communism is a ridiculous non-theorised psychologism. This is what made me say once to Bernard-Henri Lévy that he was not sufficiently anti-communist. We are still waiting for an enlightening critique of the Stalinist catastrophe. Every Day Stalinism is the only work to my knowledge which makes an interesting and informed commentary. It is an historical fact that horrible regimes legitimised themselves from Marx. It is too easy to oppose this reality by saying they were not an authentic Marxism. The question must still be asked: how was that possible? This issue, on the other hand, must not be a pretext for abandoning Marx. It is the necessary precondition for repeating the process differently; renewing this gesture whilst changing the form and not the premises. “Socialism” does not work as a term: Hitler called himself a socialist. “A true idea is divisive”, as says my friend Alain Badiou. But past errors must make use more exigent. …source

Add facebook comments

Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment