Bahrain, litmus test of Int’l tolerance for Saudi seamless brutal repression Manama to Riyadh

Shia Muslims in Saudi Arabia keep the protest movement alive

By Reese Erlich – GlobalPost – 18 March, 2013

Editor’s Note: When Arab Spring protests broke out in Saudi Arabia in 2011, the government reacted quickly. It pumped $130 billion into the economy, including hiring 300,000 new state workers and raising salaries. It also brutally cracked down on dissent, in some cases breaking up peaceful protests with live ammunition. While the carrot and stick approach worked in some cities, the Shia Muslims in the Eastern Province continued to protest. Shia make up some 10-15 percent of the Saudi population and have long rebelled against discrimination and political exclusion.

Demonstrations continued in the city of Qatif but got little publicity because foreign journalists are banned from reporting there. Correspondent Reese Erlich, on assignment for GlobalPost and NPR, managed to get into Qatif, meet with protest leaders and become the first foreign journalist to witness the current demonstrations.

This is his account: QATIF, Saudi Arabia — Night has fallen as the car rumbles down back roads to avoid the Saudi Army’s special anti-riot units. To be stopped at any of the numerous checkpoints leading into Qatif, would mean police detention for a Western journalist and far worse for the Saudi activists in the car. They would likely spend a lot of time in jail for spreading what Saudi authorities deem “propaganda” to the foreign media.

In Saudi Arabia all demonstrations are illegal, but here in Qatif residents have defied the ban for many months. At least once a week the mostly young demonstrators march down a street renamed “Revolution Road,” calling for the release of political prisoners and for democratic rights.

The anti-riot units deploy armored vehicles at strategic locations downtown. The word on this night is that if demonstrators stay off the main road, the troops may not attack.

Foreign journalists are generally denied permission to report from Qatif. Activists said this night was the first time a foreign journalist has been an eyewitness to one of their demonstrations. Asked if the troops will use tear gas, Abu Mohammad, the pseudonym used by an activist to prevent government retaliation, says, “Oh, no. The army either does nothing or uses live ammunition.”

I really hope it will be option #1.

Suddenly, young Shia Muslim men wearing balaclavas appear, directing traffic away from Revolution Road. All the motorists obey the gesticulations of these self-appointed traffic cops.

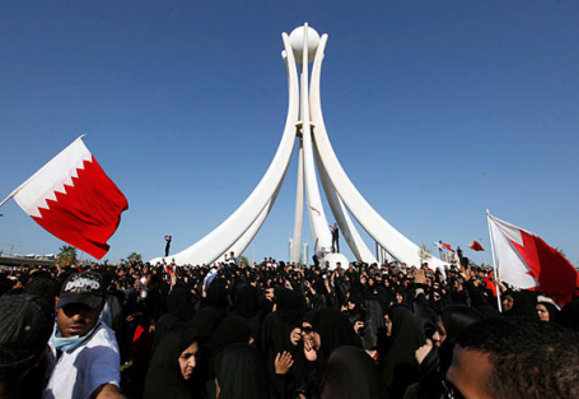

Minutes later several hundred men march down the street, most with their faces covered to avoid police identification. Shia women wearing black chadors, which also hide their faces, follow closely behind, chanting even louder than the men.

One of their banners reads, “For 100 years we have lived in fear, injustice, and intimidation.”

Despite two years of repression by the Saudi royal family, Shia protests against the government have continued here in the Eastern Province. Though Shia are a small fraction of Saudi Arabia’s 27 million people, they are the majority here. Most of the country’s 14 oil fields are located in the Eastern Province, making it of strategic importance to the government.

Shia have protested against discrimination and for political rights for decades. But the Arab Spring uprisings of 2011 gave new impetus to the movement. Saudi Arabia is home to two of Islam’s most holy cities, and the government sees itself as a protector of the faith. But its political alliances with the US and conservative, Sunni monarchies have angered many other Muslims, including the arc of Shia stretching from Iran to Lebanon.

Saudi officials claim they are under attack from Shia Iran and have cracked down hard on domestic dissent.

Saudi authorities are responsible for the death of 15 people and 60 injured since February 2011, according to Waleed Sulais of the Adala Center for Human Rights, the leading human rights group in the Eastern Province. He says 179 detainees remain in jail, including 19 children under the age of 18.

The government finds new ways to stifle dissent, according to Sulais. Several months ago the government required all mobile phone users to register their SIM cards, which means text messaging about demonstrations is no longer anonymous.

Abu Zaki, another activist requesting anonymity, says demonstrators now rely on Facebook and Twitter, along with good old word of mouth. Practically everyone at the recent Qatif protest march carried iPhones. Some broadcast the demo in near real time by uploading to YouTube.

Organizers hope their sheer numbers, along with government incompetence, will keep them from being discovered. “The government cannot follow everybody’s Twitter user name,” says Abu Zaki. “The authorities have to be selective and, hopefully, they don’t select my name.”

When protests began, demonstrators called for reforms. But now, younger militants demand elimination of the monarchy and an end to the US policy of supporting the dictatorial king.

Abu Mohammad, Abu Zaki and several other militant activists, gather in an apartment in Awamiyah, a poor, Shia village neighboring Qatif. In this part of the world a village is really a small town, usually abutting a larger city. Awamiyah is one such town, chock full of auto repair shops, one-room storefronts, and potholed streets. It is noticeably poorer than Sunni towns of comparable size.

Strong, black tea is served along with weak, greenish Saudi coffee. The protest movement in Qatif, they observe, resembles the tea more than the coffee.

Abu Mohammad tells me protests have remained strong because residents are fighting for both political rights as Saudis, and against religious/social discrimination as Shia.

Shia face discrimination in jobs, housing and religious practices. Qatif has no Shia cemetery, for example. Only four Shia sit on the country’s 150-member Shura Council, the appointed legislature that advises the king.

“As Shia, we can’t get jobs in the military,” says Abu Mohammad. “And we face the same political repression as all Saudis. We live under an absolute monarchy that gives us no rights and steals the wealth of the country.”

The government denies those claims of discrimination and repression. In Riyadh, Major General Mansour Al Turki, spokesperson for the Ministry of Interior, is the point man who often meets with foreign journalists. Al Turki is smooth and affable and practiced at the art of being interviewed by Westerners.

He dismisses Shia charges of discrimination as simply untrue. “These people making demonstrations are very few,” he tells me. “They only represent themselves. The majority [of Shia] are living at a very high level.” …more

Add facebook comments

Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment