The Betrayal of Democracy, President Obama’s failed policy on Bahrain

‘Forsaken by the West’: Obama and the Betrayal of Democracy in Bahrain

By Larry Diamond – 9 January, 2013 – The Atlantic

Of the half dozen Arab states that were shaken by popular demands for democracy when the Arab Spring erupted two years ago, Bahrain is the easiest to forget. In sharp contrast to Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, and Yemen — where dictators were toppled — (or even Syria, with its ongoing civil war), Bahrain’s authoritarian monarchy has crushed the democratic opposition. Of the six countries gripped by revolutionary fervor, Bahrain is the smallest in size and population, with most of its 1.3 million people (nearly half of them non-citizens) crowded onto an arid, largely barren island about a third the size of Rhode Island. It is not nearly as rich as its small Gulf neighbors, Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates, and its oil exports now rank a paltry 48th in the world. Among the states of the Arab Middle East, Bahrain may be the most dependent on a powerful neighbor, Saudi Arabia — which intervened militarily in March 2011 to rescue the besieged and deeply unpopular al-Khalifa monarchy.

But along with its mounting problems, Bahrain has a geostrategic trump card: location. Jutting out in the center of the Persian Gulf, less than 100 miles from Iran, it hosts the U.S. Fifth Fleet, the pillar of naval security in the region and an indispensable counterweight to Iran’s ambitions for regional hegemony.

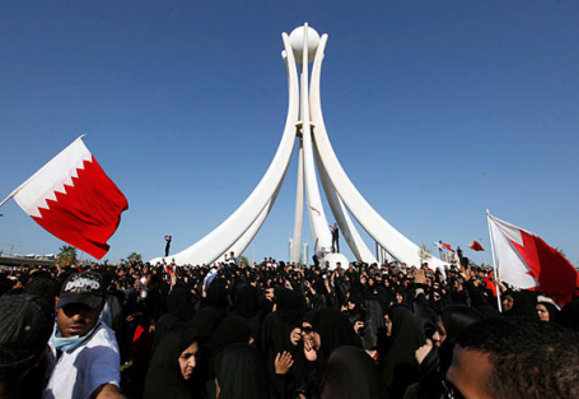

Thus, Bahrain is a major strategic ally of the United States. And so, the active mobilization into the streets of more than a quarter of Bahrain’s entire citizenry became what Al Jazeera called “the Arab revolution that was abandoned by the Arabs, forsaken by the West, and forgotten by the world.”

The United States has from time to time issued statements of concern about arrests and convictions, but always couched in the politesse of a big power with bigger issues to address.

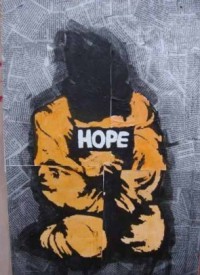

Since Bahrainis first took to the streets on February 14, 2011 to demand revision of the constitution and a transition to democracy, the United States has faced an acute and painful instance of the classic tension between security interests and moral concerns. Deeply insecure over its minority status as a Sunni Muslim monarchy reigning over a Shia Muslim majority, the Al Khalifa regime responded to the peaceful protests at the Pearl Roundabout in the capital, Manama, with force. On “Bloody Thursday,” February 17, King Hamad’s security forces raided the protestors in the dead of night, killing four and injuring some 300.

Initially, the protestors had demanded “merely” freedom, democracy, and equality (which could have preserved the monarchy on a new constitutional basis, with limited powers). Even many Bahraini Sunnis (from outside the privileged royal elite) rallied to this campaign for accountability and justice. In particular, Bahrain’s Shia majority was tired of living as second-class citizens, utterly marginalized in the distribution of power and wealth. The contrast between their hard-scrabble, high-density housing settlements and the extravagant grounds and palaces of the royal family had already been vividly documented. Five years earlier, Bahraini activists used Google Earth to display dozens of satellite images of royal properties, many of them private islands, replete with palaces, lavish swimming pools, lush gardens, yachts, and even a private golf course, race track, and hunting ground. Nevertheless, a power-sharing deal could probably have been worked out if the regime had responded to the 2011 protests with negotiations rather than repression. After all, King Hamad had assumed the throne in 1999 as something of a political reformer; he and his Crown Prince were said to remain inclined toward flexibility; and the formal architecture of an elected parliament had allowed the moderate Shia political society, Al Wefaq, to win 18 of the 40 seats in the lower house as recently as 2010.

If political reform and a negotiated settlement were an option when the protests broke out in February 2011, they were not so in the mind of the Saudi monarchy — or its hardline Bahraini allies like the prime minister and the chief of the royal court. The Saudi regime is deeply anxious about stability in its own oil-rich Eastern Province, where most of its roughly three and half million Saudi Shia are located, and where the Shia form a population majority. For the House of Saud, the prospect of a Shia-dominated government in Bahrain must have raised the specter of escalating demands for equality and dignity from Saudi Arabia’s own Shia minority.

The Democracy ReportBahrain’s Bloody Thursday cleared the Pearl Roundabout but only inflamed popular anger. Five days later, over 100,000 Bahrainis (nearly 15 percent of the indigenous population) took part in a march to honor the protestors who had been killed. As the protests escalated in size and intensity, King Hamad offered modest concessions, but too modest and too late. By then, Bahrain’s aroused majority would settle for nothing less than a purely constitutional monarchy, and militants were calling for an end to the monarchy altogether. As protests escalated further in March 2011, the monarchy called upon the Saudi-dominated Gulf Cooperation Council for assistance. In the early morning of March 17, 5,000 troops, backed up by tanks and helicopters, routed the demonstrators who had returned to the Pearl Roundabout. More than a thousand were arrested, including several leaders of the Haq Movement, which had split off from Wefaq in protest against the 2002 constitution and the latter’s decision to participate in elections. Among the arrested Haq leaders were its head, Hassan Mushaima, and a mild-mannered engineering professor and human rights activist, Abduljalil al-Singace. …more

Add facebook comments

Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment