Amidst widening of the Islamic-Secular Divide – Showdown in Egypt

Amidst widening of the Islamic-Secular Divide

Showdown in Egypt

By: Esam Al-Amin – Counter Punch

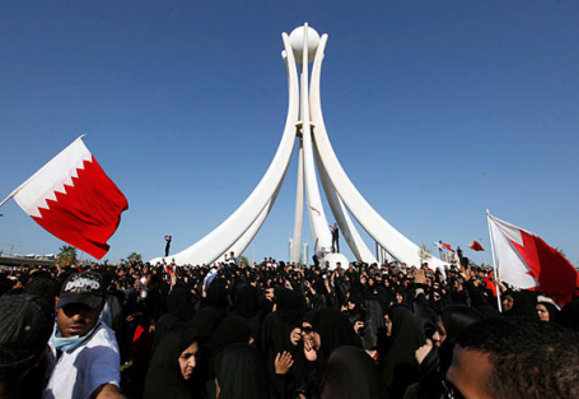

Ever since the fall of former dictator Hosni Mubarak on that fateful day in February 2011, Egyptian society and its political factions have been sharply divided. On one side is the Islamic parties led by the Muslim Brotherhood (MB) but also includes the more conservative Salafi groups as well as other smaller moderate ones such as Al-Wasat Party. On the other is a myriad of secular groups that includes many liberal, leftist, as well as youth revolutionary groups such as the April 6 movement.

There is no doubt that the unity displayed during the eighteen revolutionary days that ousted Mubarak had soon after dissipated when Egyptians went to the polls five weeks later and voted to hold parliamentary elections before writing a new constitution. The Islamic parties, which supported this referendum, won it with over seventy-seven percent of the electorate as Egyptians voted in unprecedented numbers.

The Islamic political parties reasoned that a new constitution must be written by an elected body that represents the will of the Egyptian people while the secular parties, realizing that they would be overwhelmingly outnumbered at the ballot box, argued that a new constitution must be written by representatives of all political stripes outside any claim of a popular mandate even if legitimized through elections.

Hence, throughout the tumultuous transitional period supervised by the Egyptian military that lasted over sixteen months, the gulf and mistrust between the two sides have continued to widen. Basically, there have been four main active blocs in the Egyptian political theatre, with each maneuvering to obtain or maintain an advantage over the others. They are namely: the Islamists, the secularists, the revolutionary youth, and the remnants of the old regime. Each group determined its objectives according to its general political overview or narrow interests, and tried to establish its own transient coalition with the others in order to accomplish its goals. The wild card during this political wrangling was the military, which had its own agenda and was able to play these various forces against each other.

But what were the objectives of all these players?

Feeling empowered by their vast support in the streets, the Islamists wanted to hold elections as soon as possible in order to set the agenda and dominate the discussion on the writing of the new constitution and the future direction of the country. They argued that the principles of democracy dictate no less than holding elections at all levels to embody the will of the people. Early on the Islamists established a tacit understanding with the military in order to establish a smooth transition through popular elections. In return, the military hoped to maintain stability and order while figuring out the new political landscape.

On the other hand, the secular factions, which include many traditional liberals, leftists, nationalists, and some revolutionary youth groups, as well as the Coptic Christian community, feared a possible crushing defeat at the polls since they were hopelessly divided and terribly disorganized. So their main tactic during that period was to frustrate the agenda of the Islamists while trying to impose certain constitutional principles without debate by having the military council issue several decrees and appointing several committees dominated by many of them but only to see them fail or wither away.

The main agenda of many revolutionary youth groups such as the April 6 movement, the Ultras (non-affiliated youth groups willing to confront authority), or the Egyptian Current, was to press for the revolutionary demands such as purging the Egyptian institutions from the elements of the old regime, especially in the security apparatus, the police, the media, the judiciary, as well as exposing and isolating the corrupt politicians. Throughout the transitional period they applied full pressure and maintained continuous presence in the streets in order to force the military council and its appointed government to hold trials against senior members of the Mubarak regime and those responsible for the almost 1000 people killed during the early days of the revolution. But in many instances the revolutionary youth in the streets felt betrayed by the Islamists as often times their demands and actions were met with either lip service or disdain.

Meanwhile, the remnants of the old regime, called the fulool (Arabic for remnants) stayed in the background waiting for the right moment to regroup and launch a counterrevolution. The fulool included not only many pro-Mubarak politicians from the old regime but also many corrupt businessmen and oligarchs. They knew that if a new order was allowed to be established they would lose their ill-gotten wealth and possibly face imprisonment as many prominent senior officials of the former regime had to contend with.

But the military, which control as much as thirty percent of Egypt’s economy and has been autonomous with little governmental oversight or accountability for decades, was determined to maintain this status-quo and as much of its privileges as possible. It also did not want any politicians or political groups to interfere in, let alone control, its decision-making process, especially in its internal financial conglomerates or national security affairs. So for the entire transitional period the military council pitted these groups against each other, with each group calculating and selfishly protecting its own short-term interests regardless of the overall consequences on the main objectives of the popular revolution.

With this as the backdrop the Egyptian people went to the polls seven times during this period: voting on the constitutional referendum in March 2011, four times to elect both chambers of parliament between November 2011 and January 2012, and two times to elect a president in May and June 2012.

More Egyptians went to the polls during this period than in any election in the past six decades. During the Mubarak regime the electorate had never exceeded 6 million, or less than 15 percent of eligible voters. But during the 16 months transitional period, over 62 percent of Egyptians went to the polls as 18 million Egyptians voted in the referendum, 30 million in the parliamentary elections, and 26 million in the presidential elections. Not surprisingly, in every one of these elections, the Islamist position or candidates won (77 percent in the referendum and 73 percent of parliament.)

In the presidential elections, despite the polarization that engulfed the country, the overt support of the military council, the Egyptian bureaucracy, the Supreme Constitutional Court (SCC), and the Elections Committee to the fulool candidate, as well as the massive propaganda machinery campaign against Dr. Muhammad Morsi; the Muslim Brotherhood candidate, still won though barely with 52 percent of the vote. It is important to note that both the Elections Commission and SCC were Mubarak’s appointees who also oversaw and overlooked many fraudulent elections during the Mubarak era, most notably the 2005 and 2010 rigged elections. Although it took over a week for the commission to announce the results, Morsi took office on June 30, 2012 in a polarized atmosphere. Despite the presence of the military council as the real power behind the thrown, people still had great expectations for the new president. …more

Add facebook comments

Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment