Western Funded NGOs struggle to find leverage after finding only “deaf ear” from State Department on Bahrain

Backing up rhetoric with action in Bahrain

By Stephen McInerney – 4 November, 2012 – Washington Post

Stephen McInerney is executive director of the Project on Middle East Democracy.

“Our challenge in a country like Bahrain,” Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said last November, is that the United States “has many complex interests. We’ll always have to walk and chew gum at the same time.” The growing problem is that the United States does plenty of “walking” — maintaining our strategic alliance with the Gulf kingdom in the short term — but little or no “chewing,” or taking meaningful steps to spur the political reforms needed to preserve Bahrain as an ally in the long term.

A late September vote on Bahrain’s nominee for the advisory committee of the U.N. Human Rights Council gave Washington an easy opening. In a letter to Clinton early that month, 14 nongovernmental organizations, including the Project on Middle East Democracy, Human Rights Watch and Freedom House, urged the United States to oppose the candidacy in light of Bahrain’s egregious record on human rights.

The nominee, Saeed Mohamed al-Faihani, has been a career official in Bahrain’s Foreign Ministry whose recent tenure as undersecretary for human rights coincided with the government’s brutal suppression of the country’s civilian uprising. Faihani repeatedly denied the government’s countless human rights violations, including torture of political prisoners and violent crackdowns on peaceful protests. His statements directly contradicted the findings of the government’s own Commission of Inquiry and well-documented reports by international human rights organizations.

Although Faihani resigned from his government post — days before the U.N. committee vote to meet eligibility requirements — his previous statements and blatant disregard for human rights in Bahrain gave the United States reason to question his qualifications.

Instead, the U.S. delegation was silent, and Faihani was elected by acclamation.

Bahrain quickly pointed to the election as an endorsement of the kingdom’s human rights record. King Hamad called the vote a “recognition of [Bahrain’s] democratic and political record” and evidence that Bahrain is “an oasis of human rights, co-existence, tolerance and love.” Human Rights Minister Salah Ali — Faihani’s former boss — called the unanimous total “a vote of confidence for the kingdom’s serious steps and positive role in protecting human rights.” Washington did nothing to dispute these interpretations.

The United States joined the Human Rights Council in 2009 promising to fight against “the pernicious machinations of countries seeking to obscure and deny their abuses” through the council. When Washington helped eject Libya from the council in 2011, Clinton said it was “clear that governments that turn their guns on their own people have no place on the Human Rights Council.”

More recently, U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Susan Rice highlighted successful U.S. “efforts to prevent human rights abusers, such as Iran, Syria and Sudan from winning election to the Human Rights Council.” Faihani’s position on the council’s advisory committee compromises the increased legitimacy that this work has bestowed on the council and encourages the widespread perception that the United States will confront human rights violations by Iran or Syria while ignoring the abuses of allies such as Bahrain.

A single vote against Faihani may not have kept him off the committee, nor changed the human rights situation in Bahrain overnight, but it would have demonstrated U.S. seriousness toward both the council and accountability in Bahrain.

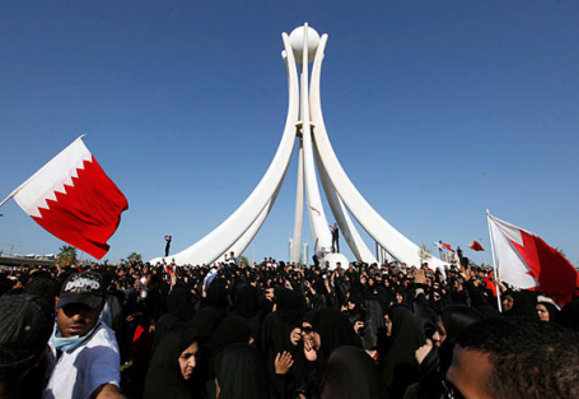

In recent weeks, Bahrain’s government has banned demonstrations of any size and upheld lengthy prison sentences given to teachers and medics for expressing their political views. It continues to crack down violently against daily protests. Washington has repeatedly expressed “concern” about the state of human rights in Bahrain, but it is increasingly clear that such statements have little or no impact.

While the Faihani vote was Washington’s latest missed opportunity to take a stand, other openings remain. The U.S. administration could limit military assistance and training to Bahrain; sanction Bahraini officials responsible for gross human rights violations; more strictly enforce the rights requirements of the U.S.-Bahrain Free Trade Agreement; or call for a special session on Bahrain at the U.N. Human Rights Council. Any of these steps would signal that Washington is finally willing to walk and chew gum, backing up its rhetoric with action.

Add facebook comments

Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment