The Failure of Nonviolence: From the Arab Spring to Occupy

The Failure of Nonviolence

28 February, 2014 – open salon – Dr Stuart Jeanne Bramhall

The Failure of Nonviolence: From the Arab Spring to Occupy

By Peter Gelderloos (2013 Left Bank Books)

Book Review

You occasionally read a totally mind bending book that opens up a whole new world for you. The Failure of Nonviolence by Peter Gelderloos is one of them, owing to its unique evidence-based perspective on both “nonviolent” and “violent” resistance. It differs from Gelderloos’s 2007 How Nonviolence Protects the State in its heavy emphasis on indigenous, minority, and working class resistance. A major feature of the new book is an extensive catalog of “combative” rebellions that the corporate elite has whitewashed out of history.

Owing to wide disagreement as to its meaning, Gelderloos discards the term “violent” in describing actions that involve rioting, sabotage, property damage or self-defense against armed police or military. In comparing and contrasting a list of recent protest actions, he makes a convincing case that combative tactics are far more effective in achieving concrete gains that improve ordinary peoples’ lives. He also explodes the myth that “violent” resistance discourages oppressed people from participating in protest activity. He gives numerous examples showing that working people are far more likely to be drawn into combative actions – mainly because of their effectiveness. The only people alienated by combative tactics are educated liberals, many of whom are “career” activists working for foundation-funded nonprofits.

Gelderloos also highlights countries (e.g., Greece and Spain) which have significantly slowed the advance of neoliberal capitalism via combative resistance. In his view, this explains the negative fiscal position of the Greek and Spanish capitalist class in addressing the global debt crisis. Strong worker resistance to punitive labor reforms and austerity cuts has significantly slowed the transfer of wealth to their corporate elite, as well as the roll-out of fascist security measures.

The Gene Sharp Brand of Nonviolence

Gelderloos begins by defining the term “nonviolent” as the formulaic approach laid out by nonviolent guru Gene Sharp in his 1994 From Dictatorship to Democracy and used extensively in the “color revolutions” in Eastern Europe and elsewhere. This approach focuses exclusively on political, usually electoral, reform. Gelderloos distinguishes between political revolution, which merely overturns the current political infrastructure and replaces it with a new one – and social revolution, which overturns hierarchical political infrastructure and replaces it with a system in which people self-organize and govern themselves.

The nonviolent approach Sharp and his followers prescribe relies heavily on a corporate media strategy to promote their protest activity to large numbers of people. This obviously requires some elite support, as the corporate media consistently ignores genuine anti-corporate protests. As an example, all the nonviolent color revolutions in Eastern Europe enjoyed major support from the State Department, billionaire George Soros and CIA-funded foundations such as the National Endowment for Democracy and the National Republican Institute.

Is Nonviolence Effective?

Gelderloos sets out four criteria to assess the effectiveness of a protest action:

– It must seize space for activists to self-organize essential aspects of their lives.

– It must spread new ideas that inspire others to resist state power and control.

– It must operate independently of elite support.

– It must make concrete improvements to the lives of ordinary people.

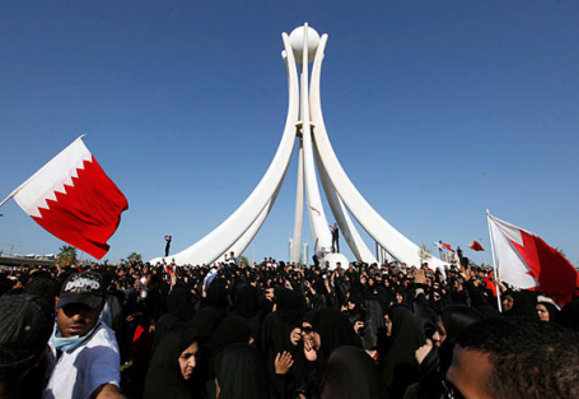

As examples of strictly nonviolent protest movements, Gelderloos offers the “color” revolutions (see 1 below), the millions-strong global anti-Iraq war protest on February 15, 2003 and 2011 Occupy protests, which were almost exclusively nonviolent (Occupy Oakland being a notable exception).

In all the color revolutions Gelderloos describes, the goal has been strictly limited to replacing dictatorship with democracy and free elections. None attempted to increase economic democracy nor to reduce oppressive work and living conditions. In fact, most of the color revolutions forced their populations to give up important protections to integrate more thoroughly into the cutthroat capitalist economy.

So-called “democracies” such as the US are just as capable as dictatorships of engaging in extrajudicial assassination, torture, and suspension of habeas corpus and other legal protections. However US corporations generally find “democracies” more investment-friendly. Owing to greater transparency, they are less likely to nationalize private industries or arbitrarily change the rules for doing business.

Besides failing to meet any of his criteria, the 2003 anti-Iraq war movement failed to stop the US invasion of Iraq and the 2011 Occupy protests failed to achieve a single lasting gain.

Successful “Combative” Protests

He contrasts these strictly nonviolent protests with nearly 20 popular uprisings (see 2 below) and two (successful) US prison riots that have incorporated “combative” tactics along with other organizing strategies. Most have been totally censored from the corporate media and history books or whitewashed as so-called “nonviolent” actions (e.g., the corporate media misportrayed both the 1989 Tiananmen Square rebellion and the 2011 Egyptian revolution as nonviolent protests).

The US, more than any other country, uses prison to suppress working class dissent. Most prison struggles employ a diversity of tactics combining work stoppages and legal appeals with property damage, riots and attacks on guards. Nonviolent protest tends to be particularly ineffective in the prison setting. A nonviolent hunger strike usually reflects a situation in which prisoners have so little personal control that the only way to resist is to refuse to eat.

Gelderloos also analyzes a number of historical combative uprisings, pointing out their relative strengths and weaknesses. He devotes particular attention to the Spanish Civil War (a failed working class revolution), the anti-Nazi partisan movements during World War II, combative Indigenous peoples resistance to European colonizers and autonomous liberated zones created in Ukraine, Kronstadt, and Siberia following the Bolshevik Revolution and in the Skinmin Province of Manchuria in pre-World War II China.

Who Are the Pacifists?

He devotes an entire chapter to the major funders and luminaries of the nonviolent movement. Predictably most of the funding comes from George Soros, the Pentagon, the State Department and CIA-funded foundations such as USAID, NED, and NIR. Among other examples, Gelderloos describes the Pentagon running a multi-million dollar campaign to plant stories in Iraqi newspapers to promote “nonviolent” resistance to US occupation. …more

March 3, 2014 No Comments

No Love for the Black Power Movement, Misrepresenting the Civil Rights Movement

No Love for the Black Power Movement, Misrepresenting the Civil Rights Movement

26 August 2013 – by Lawrence Brown

How far have we really come?

As we sit on the eve of the 50th anniversary of the magnificent March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (MOW), I am struck by a peculiar phenomenon: the Black Power phase of the African American struggle for liberation gets no love. Most of our remembrance and recognition of the MOW derives from the landmark Civil Rights (1964) and Voting Rights (1965) Acts that were passed in its wake. With the Supreme Court a few weeks ago invalidating key provisions of the Voting Rights Act, we are reminded of the brave sacrifices of those select civil rights soldiers who marched, sat, and confronted Jim Crow for critical rights.

But just like Americans tend to truncate the life and message of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. after his “I Have a Dream” speech, our recollection of the history of the struggle against America’s myriad forms of oppression against black folk also seems to stop at that critical point. Even when we do remember the period following 1963, we do so derisively. Case in point is the recently released movie “Lee Daniel’s The Butler,” which depicts the Black Power phase of the African American struggle for liberation in a cartoonish and nearly derogatory manner.

One area that represents a clear superficial reading and novice understanding of both movements is the fact that both Dr. King and Huey P. Newton (founder of the Black Panther Party) assailed the merits of capitalism. As we continue the push for jobs and seek to close employment gap by race, most mainstream current civil rights activists have all but lost sight of King’s and Newton’s laser-sharp critique of capitalism. In his book Strength to Love, Dr. King argued:

[W]e must admit that capitalism has often left a gulf between superfluous wealth and abject poverty, has created conditions permitting necessities to be taken from the many to give luxuries to the few, and has encouraged small-hearted men to become cold and conscienceless so that…they are unmoved by suffering, poverty-stricken humanity.

In his autobiography Revolutionary Suicide, Huey P. Newton proclaimed:

I have no doubt that the revolution will triumph. The people of the world will prevail, seize power, seize the means of production, wipe out racism, capitalism, reactionary intercommunalism—reactionary suicide. The people will win a new world…. If the world does not change, all its people will be threatened by the greed, exploitation, and violence of the power structure in the American empire. The handwriting is on the wall. The United States is jeopardizing its own existence and the existence of all humanity.

While both King and Newton decried capitalism’s overall ability to create sustainable, healthy, and prosperous economic conditions, most of the mainstream civil rights leaders participating in the anniversary marches this week embrace capitalism and offer no serious challenge to the corrosive and cancerous nature of America’s economic system. American capitalism—which is rooted in Wall Street oligarchy and corporate plutocracy—threatens the economic well-being of all Americans, not just black folk. But when American capitalism combines and intertwines with structural racism, it creates the dastardly racial disparities in not only employment, but in wealth, which is the most important indicator of economic health.

By April 4, 1967, Dr. King had connected the dots between civil rights and human rights. He had made the leap between domestic policy and foreign policy. He would traverse the philosophical chasm the artificially separated the Civil Rights and Black Power movements when he preached in his sermon “Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence”:

I am convinced that if we are to get on the right side of the world revolution, we as a nation must undergo a radical revolution of values. We must rapidly begin…we must rapidly begin the shift from a thing-oriented society to a person-oriented society. When machines and computers, profit motives and property rights, are considered more important than people, the giant triplets of racism, extreme materialism, and militarism are incapable of being conquered.

Exactly a year later, Dr. King was gunned down in Memphis. A coincidence? I think not. Dr. King had joined the rising chorus of a radicalized Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and Black Panther Party in bearing witness to the dangers of America as empire, not merely as a nation. America as empire threatened the whole world and all human life. America as empire extracted wealth from “Third World” nations, propping up brutal dictators, causing nations to be underdeveloped, and hundreds of millions to starve. Most of the mainstream leaders today offer no sustained ethical critique on the level of King and Newton.

There is another sense by which we oversimplify the narrative of the Civil Rights and Black Power movements: the myth of nonviolence as a winning strategy. Author Lance Hill lays this myth to rest in his spectacular book The Deacons for Defense: Armed Resistance and the Civil Rights Movement. What defeated the terror organization known as the Ku Klux Klan in the South was not nonviolence! It was a band of organized black men known as the Deacons for Defense and Justice. When black men began to arm themselves and show their willingness to defend themselves against Klan- and police- inflicted terrorism, that is the point when the federal government stepped into prevent massive bloodshed and crushed the Klan.

Most people also don’t recall the level of racial terrorism endured by black folks during the time of the Civil Rights movement. Less than a month after the March on Washington, four little girls (Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley, Carole Robertson, and Denise Miller) were killed in the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing. Less than three months before the March on Washington, Mississippi civil rights leader Medgar Evers was assassinated in his own driveway by a member of the White Citizens’ Council, Byron De La Beckwith. This is the type of naked terrorism that the Deacons for Defense were able to confront and defeat in the South, although many Black Panthers were killed in other areas of the country by the FBI’s anti-black domestic terroristic operation known as COINTELPRO. Thus, we often forget the way in which the federal government functioned as both a saint and sinner with regards to the Civil Rights and Black Power movements.

Another way in which we oversimplify the struggle for Civil Rights and Black Power is that we neglect to give due credit to their precursors. …more

March 3, 2014 No Comments

The Use of Guns in the Civil Rights Movement in the United States

Deacons for Defense and Justice

The Use of Guns in the Civil Rights Movement

By Ben Garrett

The thought of guns during America’s Civil Rights movement generally conjures up images of acts of violence perpetrated against African-Americans and civil rights workers in the South. But guns also played a significant role in dissuading violence, primarily through the actions of the Deacons for Defense and Justice.

A Call to Arms

On July 10, 1964, eight days after the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Earnest Thomas and Frederick Douglas Kirkpatrick assembled a group of African-American men in Jonesboro, La., forming the Deacons for Defense and Justice (DDJ).

Although the Civil Rights Act outlawed discrimination, federal enforcement was lacking and the Ku Klux Klan was alive and well in the Deep South. Volunteers for the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) were facing resistance — often in the form of violence — as they attempted to register black voters. Thomas, Kirkpatrick and those who joined their cause were intent on thwarting violence by the Klan and similar factions while providing protection for the CORE volunteers and other civil rights workers.

In contrast to the message of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights leaders, who stressed a peaceful approach, DDJ encouraged African-Americans to arm themselves for self-defense. The group did not promote violence; rather, they recruited members to carry guns in order to protect themselves and those working on their behalf. It was in defiance of CORE’s nonviolent terms that Thomas, a military veteran, began going armed while guarding CORE’s freedom house in Jonesboro from Klan attacks.

It has been written that Deacons carried a variety of guns, ranging from handguns to military-style carbine rifles to shotguns.

A Movement Takes Hold

Working discretely — members often kept their DDJ affiliation a secret — the group soon began a chapter in Bogalusa, La. Other chapters followed, until DDJ had a presence in Mississippi and Alabama in addition to their chapters in Louisiana. The group inflated its numbers as a means of intimidation, claiming to have 50 chapters across the region. An FBI investigation revealed the organization was much smaller, though it is generally accepted that DDJ had 21 chapters across the three states at its peak.

The armed self-defense movement was not without resistance. As DDJ’s popularity increased, the FBI began an investigation into the group’s activities. Agents routinely interrogated DDJ members. Before the DDJ’s founding, NAACP volunteer Robert Williams faced significant opposition when he armed his North Carolina chapter of the NAACP. Some of that opposition came from the NAACP itself. Williams was ultimately forced to seek refuge in Cuba.

Despite the resistance, the DDJ’s efforts were effective. In 1966, King was convinced to allow Deacons to provide security for the March Against Fear from Memphis to Jackson, Miss. In his book The Deacons for Defense: Armed Resistance and the Civil Rights Movement, Southern Institution for Education and Research Executive Director Lance Hill wrote that Deacons helped diffuse a potentially violent situation at a Jonesboro high school. When picketing black students had fire hoses turned on them, DDJ members began loading shotguns in view of police officers stationed at the school. Officers responded by turning away the fire trucks.

Perhaps most importantly, the DDJ forced enforcement of the Civil Rights Act after armed Deacons tangled with Klan members in Bogalusa. As a result, federal authorities forced the Klan in the area to disband in a move that was symbolic of the direction in which the civil rights movement was headed.

No longer able to attack African-Americans without fear of retaliation from gun-wielding Deacons, the Klan began to lose its power-hold on the region. Local and state authorities that had been reluctant to enforce the 1964 Civil Rights Act had little choice but to react to the DDJ’s presence. In 1966, Louisiana Gov. John McKeithen required Jonesboro officials to diffuse the city’s racial disputes.

Post-Civil Rights Involvement

With the Civil Rights Act being enforced and the threat of violence greatly diminished by the late 1960s, the Deacons for Defense and Justice’s visibility declined. After 1968, the DDJ was essentially inactive. …source

March 3, 2014 No Comments

Reconciling the role of armed resistance in the midst of MLKs “nonviolent” movement

Deacons for Defense and Justice

Wikipedia

The Deacons for Defense and Justice was an armed self-defense African-American civil rights organization in the U.S. Southern states during the 1960s. Historically, the organization practiced self-defense methods in the face of racist oppression that was carried out under the Jim Crow Laws by local/state government officials and racist vigilantes. Many times the Deacons are not written about or cited[citation needed] when speaking of the Civil Rights Movement because[citation needed] their agenda of self-defense – in this case, using violence, if necessary – did not fit the image of strict non-violence that leaders such as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. espoused. Yet, there has been a recent debate over the crucial role the Deacons and other lesser known militant organizations played on local levels throughout much of the rural South. Many times in these areas the Federal government did not always have complete control over localities to enforce such laws like the Civil Rights Act of 1964 or Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The Deacons are a segment of the larger tradition of Black Power in the United States. This tradition began with the inception of African slavery in the U.S. and with the use of Africans as chattel slaves in the Western Hemisphere. Stokely Carmichael defines Black Power as: “The goal of black self-determination and black self-identity—Black Power—is full participation in the decision-making processes affecting the lives of black people, and recognition of the virtues in themselves as black people.”[1] “Those of us who advocate Black Power are quite clear in our own minds that a ‘non-violent’ approach to civil rights is an approach black people cannot afford and a luxury white people do not deserve.”[1] This refers to the idea that the traditional ideas and values of the Civil Rights Movement placated to the emotions and feelings of White liberal supporters rather than Black Americans who had to consistently live with the racism and other acts of violence that was shown towards them.

The Deacons were a driving force of Black Power that Stokely Carmichael echoed. Carmichael speaks about the Deacons when he writes, “Here is a group which realized that the ‘law’ and law enforcement agencies would not protect people, so they had to do it themselves…The Deacons and all other blacks who resort to self-defense represent a simple answer to a simple question: what man would not defend his family and home from attack?”[1] The Deacons, according to Carmichael and many others, were the protection that the Civil Rights needed on local levels, as well as, the ones who intervened in places that the state and federal government fell short. …more

March 3, 2014 No Comments

Police Violence, Resistance and The Crisis of Legitimacy

Police Violence, Resistance and The Crisis of Legitimacy

Kristian Williams – January 2011 – Solidarity

ON SEPTEMBER 5, 2010, Los Angeles police shot and killed a Guatemalan day laborer named Manuel Jamines.

The next day, a crowd gathered on the corner where Jamines died. They assembled a small memorial, then piled debris and set fires in the street, and hurled rocks and bottles at the cops, reportedly injuring several.

Police responded with rubber bullets and tear gas; they arrested more than two dozen people. Rioting continued for three nights running.

Police claimed that Jamines was threatening passers-by with a knife — a story widely disbelieved in the Latino community and contradicted by eyewitness accounts. “I did not see a knife in his hands,” one witness told reporters.(1)

“He had nothing in his hands,” another confirmed; “At the moment when the police were shooting, he had nothing.”(2)

Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa promised an investigation, and simultaneously voiced his support for the police. “These guys are heroes,” he said.(3)

Los Angeles is the most recent site of a multi-city policing crisis affecting the entire West Coast. What clearly sets a number of recent cases apart is not the fact of police violence, but the fact that that violence is being challenged. The controversy, in other words, is not only about violence, but about authority. It is a crisis of legitimacy.

In Oregon and Washington, as well as in California, an assortment of legal proceedings, peaceful marches, riots, and repeated attacks against police and their property all point to the contested nature of police violence and the slow normalization of violence in response.

Oakland: Exceptional Symbols

Oakland, California set the tone: On New Year’s Day, 2009, transit police killed an unarmed Black man, Oscar Grant, in front of numerous witnesses. Video of the incident shows Grant lying facedown, his hands behind his back.

One cop, Tony Pirone, can be heard calling him a “bitch-ass nigger;”(4) another cop, Johannes Mehserle, draws his gun and shoots Grant in the back, point-blank.

Grant’s killing sparked a series of protests and small riots. Largely in response to the rebellion, the authorities arrested Mehserle and charged him with murder.(5)

More than a year later, in July 2010, Mehserle was convicted — not of murder, but of involuntary manslaughter. The response of the community, once again, was outrage expressed in marches, barricaded streets, broken windows, dumpster fires, and looting; damages were estimated at $750,000.(6) Mehserle was sentenced in November to just two years in prison, provoking further unrest.

It was barely two months after Grant’s shooting, in March 2009, that a Black ex-con named Lovelle Mixon killed two Oakland cops at a traffic stop, and then two more during the SWAT raid to bring him in. Mixon died in the shoot-out.

These two cases immediately came to symbolize the tense relationship between Blacks and the police — a relationship often defined by violence. Yet both cases are also exceptions to the usual pattern, though they are exceptions for very different reasons.

Grant’s case is exceptional, practically unique, because police are so rarely punished for their violence; Mixon’s because, in the conflict between African Americans and police, the casualties are usually all on one side.

Washington State: “We will fight!”

Further north, in Washington State, at least nine cops have been shot since Halloween, 2009; six of them died.(7)

In a way, the chain of events began on November 29, 2008, when King County Deputy Paul Schene beat a teenaged girl in a holding cell. The following February, the deputy was charged with assault and a videotape of the incident was released. He was fired that September, and later tried — but not convicted. …more

March 3, 2014 No Comments