Bahrain’s Mythical Democratic Reform and Human Rights Charade

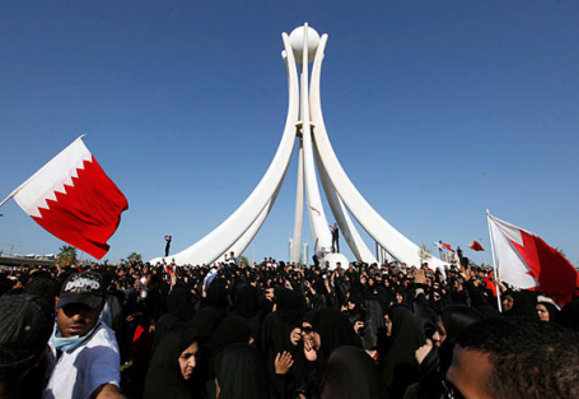

Bahrain had a longstanding consensus in favor of moderate reform, including reinstating a constitutional monarchy that has never really been. Last February’s State inflicted violence on peaceful protests has likely closed the window on a long history of the al Khalifa regime’s promises, offers and actions that have never materialized. King Hamad has been out maneuvered by a Well Educated, Techno-Savvy Opposition that has brought new light to his unceasing deceptions and the violent complicity in his misdeeds by the West. To contrast the present conundrum and extent of lies, manipulation and deceit from the al Khalifa regime, here is a revisit of recent history with this 2002 article from Middle East Intelligence Bulletin…

Political Reform in Bahrain: The Price of Stability

September 2002 – by Nadeya Sayed Ali Mohammed – MEIB

Nadeya Sayed Ali Mohammed is a post-doctoral research fellow at York University in Canada, a contributing writer for Oxford Analytica.

King Hamad bin Isa al-Khalifa’s August 21 decree establishing the district boundaries for Bahrain’s parliamentary elections in October was emblematic of the entire political reform process that has been underway for the past year and a half. Although it was greeted with much fanfare by supporters of the monarchy, Shi’ite Muslim opposition leaders complained that the single-member districts did not take into account the country’s “demographics” – a polite way of pointing out that it dilutes the votes of Shi’ites, who constitute 65% of the population. The gerrymandering was so blatant that some districts contain as many as 12,000 registered voters, while others have as few as 500.

While Hamad’s decree highlights that there is a limit to Bahrain’s political liberalization drive, the opposition’s relatively muted reaction illustrates its primary objective – stability. The king’s strategy is intended not so much to satisfy the political demands of his constituents, but to ensure that they are expressed within the system, rather than in the streets.

The National Charter

Hamad’s ascension in 1999 originally met with considerable Shi’ite apprehension. He had served as crown prince and defense minister during the 38-year reign of his father and played a key role in the brutal suppression of Shi’ite protests from 1994 to 1998. He also faced a potential challenge from his uncle, a staunch opponent of reform who had once supported the ascension of his own son. In an effort to secure his position, Hamad sought to ease tensions and promote reconciliation by gradually releasing political prisoners during the first two years.

Preserving internal stability required additional measures – the restoration of parliament, which was dissolved in 1975, had long been a key political demand of Shi’ite opposition leaders. Political reforms were also seen as a way to bolster the country’s standing internationally. With its small population and meager resources, Bahrain’s influence within the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) was limited, and its only strategic importance derived from its location as the home of the US Fifth Fleet. Moreover, Qatar had scored points internationally by holding municipal elections in March 1999. Hamad clearly wanted to put Bahrain on equal footing with its centuries’ old rival, perhaps with an eye toward influencing the ruling of the International Court of Justice on the two countries’ dispute over the Hawar Islands (which were awarded to Bahrain in March 2001). Improving relations with Iran, a predominantly Shi’ite country, was also an important consideration.

Economic conditions also required some measure of political reform. Despite much talk about diversifying the economy and strengthening sectors such as financial services, tourism, aluminum smelting, petrochemicals and ship repair, Bahrain continued to depend on its small and dwindling oil resources, which account for over 60% of government revenue, and aid from Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Kuwait, which accounts for 20%. The government has been unable to address the needs of the lower and middle classes by reducing unemployment, improving its provision of social services, and developing the private sector. These issues, exacerbated by the inequitable distribution of opportunity, were central to Shi’ite discontent and contributed to the riots of 1994-98. The legacy of this instability was reduced investment and dwindling consumer spending. The government hoped that political reform would bolster investor and consumer confidence and thereby boost the economy.

In December 2000, Hamad appointed a committee to draft a National Charter, which outlined four political “reforms”: the creation of a bicameral parliament with an upper house of appointed “experts and scholars” and a lower house with elected members; the granting of full suffrage to male and female citizens; the creation of an independent judiciary, the post of attorney-general, and a “public accountability council”; and Bahrain’s transformation into a “constitutional hereditary monarchy,” with the emir as king.

The National Charter was sharply criticized by the London-based Bahraini opposition on a number of grounds:

The change of the emir’s title to king appeared to codify the Khalifa family’s position as Bahrain’s ultimate authority.

The lower assembly, though elected, would not have any law-making powers.

The process of preparing the charter did not involve public consultation.

It excluded longstanding opposition demands for the legalization of political parties and labor unions; acceptance of Shi’ites into sensitive government and security positions; the return of deported opposition leaders; and the release of all political prisoners.

Economic justice and the “Islamization” of public life were not addressed.

In response to these criticisms, Hamad decided to submit the charter to a referendum. He also issued an amnesty for most political prisoners, ended the house arrest of Shi’ite opposition leader Sheikh Abdul Amir al-Jamri, granted permission for the return of 108 people in exile and guaranteed that the lower house would have full law-making powers. Following this, the opposition gave the charter its blessing and urged the population to support the referendum. Despite its limitations, many Bahrainis supported the prospect of change as an alternative to the status quo. However, at the same time, many also feared that the referendum was a means for the security apparatus to identify discontented elements (this perception was reinforced when voters’ passports were stamped – making boycotters readily identifiable in the future). Fearing reprisals, perhaps, 90% of the population went to the polls on February 14-15, 2001, with 98% of voters supporting the charter.

The charter nevertheless remained ambiguous. It neither specified the role of the elected assembly vis-a-vis the chamber dissolved in 1975, nor the role and powers of the legislature as a whole in relation to the executive. The size of the proposed chambers was not specified, nor was there any indication of how differences between them would be resolved. No target date for elections was specified. Furthermore, the charter specified that the king would have the authority to appoint and dismiss the prime minister and cabinet.

Following the referendum, Hamad implemented a number of additional reform measures: repealing the 1974 Penal Code, abolishing the State Security Court (established in 1972 and extended in 1995), ordering all those removed from state jobs for political dissent to be rehired, and granting citizenship to more than 10,000 bidun (non-national residents, mostly of Persian origin).

He also appointed a National Action Committee (NAC) to implement the charter and draft amendments to the 1973 constitution. That this was done unilaterally before calling parliamentary elections clearly underscored the undemocratic and closed nature of the reform process . The constitution requires that amendments be approved by the legislature.

In April , Hamad announced a cabinet reshuffle, ostensibly to bring in qualified figures, reduce corruption and instill public trust in the government. In fact, the most important portfolios (defense, interior, foreign, and oil) remained unchanged, while the five new additions to the cabinet included several key individuals who were involved in or heavily supported the 1995-96 crackdown (Education Minister Muhammad Al Ghatam, Information Minister Nabil al-Hamir, and Minister of State for Foreign Affairs Muhammad Abd al-Ghaffar). At the same time, the Shi’ite ministers had their responsibilities curtailed, while Sunnis continued to control the key ministries (nine were controlled by the Khalifa family alone). Moreover, a number of under-secretary positions were created within the ministries to accommodate the younger Khalifas.

On the first anniversary of the referendum in February 2002, Hamad made an official announcement giving his assent to the constitutional amendments made by the NAC; declared the Gulf island of 600,000 to be a kingdom with himself as reigning sovereign; and declared that national elections for a legislative body would be held on October 24 and municipal elections on May 9.

The announcement also stipulated that both chambers in the bicameral legislature will have equal power in terms of legislation. This means that, in practice, the king can exercise veto power through his control of the appointed chamber. This contravenes the 1973 constitution, which gave an elected legislature the exclusive right to pass laws.

A number of subsequent decrees were apparently intended to undercut the electoral prospects of Shi’ite candidates. In the municipal elections, for example, nationals of the six GCC States who are resident on the island and others who own property in Bahrain (mostly Sunnis) were granted the right to vote. Shi’ite Islamist candidates still managed to win 21 out of 50 seats in Bahrain’s five civic councils, prompting additional measures to dilute Shi’ite votes in advance of the parliamentary elections.

In July 2002, a new citizenship law was introduced to allow individuals from the neighboring countries to obtain Bahraini citizenship (also aimed at reducing the Shi’ite majority in the electorate). A political rights law issued around the same time bars all unions, social organizations and political associations from “participating in any electoral campaign on behalf of any candidate” and prohibits campaigning in religious places, universities and schools, public squares, roads and government buildings (which works to the disadvantage of Shi’ites, who have fewer alternative outlets to mobilize support).

Conclusion

The 2001 referendum dramatically eased tensions and dissatisfaction among Bahrainis and the public mood was clearly been buoyed by improvement in the human rights situation and the promises of further reform. Some of this initial euphoria dissipated after the cabinet reshuffle, however, as it became clear that the reform process itself lacked transparency.

Most of the bona fide reform measures that have been implemented so far are not democratic advances, per se, but human rights advances. The general amnesty for political prisoners and exiles, the reinstatement of dissidents fired from public sector jobs, the lifting of travel bans on political activists, and the abrogation of state security laws have all created more opportunities for political expression. However, the bodies set up to suppress the opposition in the mid-1990s (the Special Investigation Service, the Criminal Investigation Directorate, and the Public Security Force) remain intact and under the control of the emir’s uncle and prime minister, Sheikh Khalifa bin Salman al-Khalifa, an anti-reform hard-liner.

A second important limitation to the reforms is that they have been granted in a patrimonial fashion. Bahrain’s reform process commenced as a unilateral royal initiative and continues to be portrayed as a grand gesture from the king to his people. Most of what passes for economic reforms (e.g., the reduction in university fees, a modest assistance program to aid the unemployed, exemptions in housing loan installments, and an extra month’s pay for state employees) were announced personally by the King, as if they were “handouts” for which his subjects should be grateful, and promulgated without regard to their inflationary effects or the strain they may place on the public purse.

Similarly, political liberalization measures have been bestowed upon the population by royal decree and Hamad remains reluctant to consult with any political groups outside of government on the reform process. Only he has the power to chart its future, its parameters, its intensity and its extent. He also has the power to determine what social groups and what opposition networks are to be included in or excluded from the reform process.

The formal establishment of the monarchy and the undemocratic amendments to the constitution reinforced the belief that the political reform process in Bahrain was to benefit the Khalifas, rather than the people. That the first two articles of the February 2002 decree changed the name of Bahrain into the “Kingdom of Bahrain” and the title of Emir into King (with elections being mentioned third) hints at the priorities of the reform process and its creator. In retrospect, the reforms can be viewed as ad hoc measures responding to a crisis of legitimacy stemming from chronic fiscal difficulties, international democratization and domestic pressures.

The liberalization package was formulated as part of a pre-emptive strategy to provide the regime with stability – only as much political reform measure as necessary to appease opposition groups, without alienating the ruling family or any of the pillars of his power. Yet even this limited liberalization could generate its own momentum. As more become aware of their enhanced collective civic power, they are likely to act to expand the parameters of liberalization by pressing for additional, and possibly far-reaching, reforms. It is open to question whether the regime can withstand the strains that would likely emerge once the political reforms are translated into practice and start affecting the ruling family’s privileges. Sheikh Hamad may soon realize that, as people gain more freedom and voice, the price of continued political stability will exceed ad hoc initiatives and handouts. …source